- Home

- Teachings (1)

- Teachings (2)

- Teachings (3)

-

Rav Kook's Journals

- From My Inner Chambers

- Thirst for the Living God

- The Pangs of the Soul

- Yearning to Speak a Word

- Singer of the Song of Infinity

- Wellspring of Holiness

- I Take Heed

- To Know Each of Your Secrets

- Great is My Desire

- To Serve God

- To Return to God

- Land of Israel

- My Love is Great

- Listen to Me, My People

- Birth Pangs of Redemption

- New Translations

- Lights of Teshuvah

- About the Translator

- Contact Me

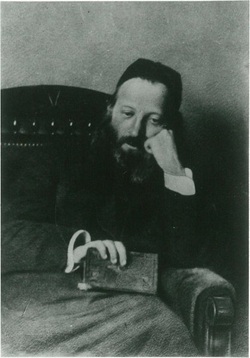

Rav Kook

What Rabbi Kook Was

by Rabbi Dovid Hacohen (the Nazir)

People speak and write without end about what Rav Kook was. But no matter how much they write and speak, no one can reveal what he was, because he transcended anything that one could say of him.

Rabbi Dovid Hacohen (the Nazir), Likutei Harayah, p. 17

A Good Jew

by Rabbi Yisrael Porat

Usually, a person who has become famous is treated with awe and respect by those who are far from him and have an exaggerated idea about him. But when they come to know him better, their impression diminishes. They see many things that are understandable and not so wondrous. Everyone has weaknesses and failings.

But Rav Kook was different. The more you stood in his presence, the more you saw how he conducted himself, the more you heard him speak, the more did he rise beyond your comprehension. You came to honor and respect him, to roll in the dust of his feet. Before you, you saw the immense phenomenon of a giant, a man with a mind that was encompassing and penetrating, a “good Jew” [a tzaddik] in the full meaning of the word, and a man in his full stature.

Likutei Harayah, p. 17

A Visionary

by Prof. S. H. Bergman

Rav Kook was a great visionary. In his mind’s eye, he saw many things that we cannot. But he did not know how to control the flow of his visions and to arrange them in accordance with an ordered philosophical system.

Nevertheless, each of his small essays is filled with lightning flashes, and from that viewpoint it surpasses methodical presentations. This drawback of methodology and order is a great stumbling block to those who try to explain his thoughts to others. But this does not detract from the great wealth of his visions.”

Likutei Harayah, p. 40

Not Because I Have the Strength

Rav Kook once wrote, “I write not because I have the strength to write, but because I do not have the strength to remain silent.”

Likutei Harayah, p. 43

The Rabbi of the Era

by Rabbi Alter Yaakov Shachrai

The acute writer, Rabbi Alter Yaakov Shachrai wrote regarding Rav Kook’s unique post as chief rabbi of the entire land of Israel. This was in 5685 (1924), when Rav Kook returned from his trip to the United States, which had made such a great impression. This article was printed in Ha’aretz:

“Rav Kook is the rabbi of all of the land of Israel—not because the committee of rabbis and representatives of the communities from Dan to Be’er Sheva appointed him as head of the rabbis. He is the natural rabbi of the land of Israel because in our generation, there is no one amongst all the rabbis of Israel as fit as he for that post. Therefore this merit is his alone.

“The people of Israel are not orphaned of great rabbis, pure of heart and of elevated character. But the land of Israel has found its rabbi, its spiritual leader and religious teacher, only in Rav Kook.

“He is the rabbi of the era. Whoever has seen Rav Kook stand on stage and speak with grandeur, whoever has read his works and seen the lights and illuminations flashing and rising from the lines must realize that here the generation’s spiritual and religious leader speaks to it, that here the prophet of the spiritual and religious renewal speaks to it.”

Chayei Harayah, p. 162

A Gushing Wellspring

by Rabbi Eliezer Cohen

Rabbi Eliezer Cohen of Jerusalem told me:

From the time that I was quite young, I always ran to hear the talks of Rav Kook. Even then, I felt that he is like a gushing wellspring, and I realized that he did not say anything that he had prepared ahead of time, but that his words were new even as he spoke.

Once he spoke in Yeshiva Eitz Chaim, juxtaposing many statements of Rabbi Meir from in the Talmud. The great scholars there were astonished at his amazing memory and breadth of thought.

“In this great man of Israel were combined abilities that usually do not appear together: his memory was extraordinary. On his lips were not only the Bible and Talmud, but also the language of the Zohar, of Rambam, and so forth. And with that, he was also a well of original ideas. When his wellspring began to flow, it was difficult for him to interrupt it. Whoever touched upon any halachic or aggadic statement, in revealed or mystic teachings, or in ethical teachings, his wellspring began to pour forth almost without constraint. The current of his thoughts flowed without limit. Even more astonishing, all his talks and speeches, whether in intricate Talmudic discussions, whether ethical talks and ideas, were given without preparation. He once wrote, ‘I write not because I have the strength to write, but because I do not have the strength to remain silent.’ We saw that he would interrupt his words and his writing not because he had no more to say and to write, but because that he had to at last stop”

Rabbi Y. M. Tukatzinsky, Shaarei Zion, Sivan-Elul 5696 (1936), Likutei Harayah, p. 43

More Thought

The poet Uri Tzvi Greenberg once told Rabbi Moshe Tzvi Neriah: “One section of Rav Kook’s Orot Hakodesh contains more thought than entire books written by non-Jewish thinkers.”

Malachim Kivnei Adam, p. 373

A Voice Coming from Heaven

by Professor Haim Lifshitz

Rabbi Dov Ber, one of the early students at Merkaz Harav, told the following:

I was a boy when I first came to Merkaz Harav. But the image of Rav Kook has never left me, from then until this day. Rav Kook used to teach in the yeshiva in a loud voice. Every word that he pronounced was clear and distinct, as though you were listening to a voice coming from heaven. I felt in my heart as though I understand everything that I heard from his mouth, in halachah and in philosophy.

And Rav Kook’s ability to explain was extraordinary. The moment he looked at you and opened his mouth, you felt as if you were standing before the ultimate truth, and that you were hearing Torah from Mt. Sinai. His words were joyous, and they made the heart rejoice.

Today, when you read Rav Kook’s writings, it is hard to understand the difficult style. You have to read the words through twice and three times, in order to understand their meaning. And not everyone can understand what he reads.

“But then it was different. Rav Kook would pour forth ideas, thoughts and words. His only desire was to give: to give of his wealth, of himself and of his being, to impart to others from who he was.”

Shivchei Harayah, p. 175

The Letter of a Young Idealist

by Rabbi Tzvi Yehudah Kook

Rav Kook’s only son, Rabbi Tzvi Yehudah, sent the author Yosef Chaim Brenner his father’s work, Ikvei Hatzoan, accompanied by a letter in which he explained his father’s teachings and attitude to the Zionist aliyah and the religious old guard of Jerusalem. The letter was sent in 1907. Brenner was living in London, and employed as editor of Hameorer. Rabbi Tzvi Yehudah was at the time only seventeen years old.

I request that you not only read this book but study it deeply and respectfully. Superficiality is harmful to understanding the intent of words of deep wisdom. When you read it over and over again, I believe that you will gain new insights and even new ways of viewing the world. I am sending you this book not to sell it or because the author is my father and I love my father’s ideals and wish to see them publicized. Rather, I send it to you as a member of our young generation, one of the idealists who sends a sweet gift to someone who I have heard of as someone like me and close to my spirit.

In explanation of the book, let me tell you that my father is one of the most pious rabbis. Besides being a genius in Torah, he is also a tzaddik. Nevertheless, at the same time he is a philosopher whose thought tolerates no obstacles whatsoever. He has deeply investigated and studied the teachings of the non-Jewish philosophers, penetrated the foundations of our Torah and come to the inner chambers of the kabbalah.

With a torn and upset heart, he has seen and understood how his nation, which he loves so deeply, is broken and torn to shreds. And he has come to recognize the source of these evils as a lack of recognition of Jews for each other, of their distance from each other, their inability to truly appreciate each other’s gifts and ideals. The elders of Judaism have been identified with a hatred of life, with laziness, and other such traits. On the other hand, the elderly view those who seek enlightenment, wisdom and animated yearnings as synonymous with heresy, apostasy and a contempt for the holy....

The breaches that this have caused have broadened to such a degree that our situation today is worse than it has ever been.

Three years ago, my father came to the land of Israel and saw the full ugliness of this breach. He decided to mount the community podium and work for the good of his people with all his strength. With his eloquent pen, he publishes his thoughts in many forums, and with his articulate speech, he communicates with those who are fit.

Despite his many obstacles—in particular, from the older generation—he has already accomplished much. For instance, he has set up a vocational center in the Talmud Torah here in Yaffa, in order to teach the students crafts. Whoever lives here knows how great a step that is.

Young individuals have answered his call here and outside the land. His influence of the new generation, which recognizes his unique worth, has been great. He stands as the touchstone between the two sides, bringing forth the good in each, and seeking to bring them together and to make them recognize each other as brothers. Most of all, he wishes Judaism, its character and its details to be understood.

Malachim Kivnei Adam

How Rav Kook Relaxed

by Rav Moshe Tzvi Neriah

Rav Kook once explained:

When the philosopher Kant wanted to relax from his philosophical investigations, he studied geography. He would say, “Since I am a man of abstractions, I relax and renew my energy when I study concrete things, such as mountains, rivers, cities, towns, and so forth.”

I am like that too. By nature, I am a man of thought and feeling. When I need to relax, I learn halachah, and then I feel that my feet are standing on solid ground.

Likutei Harayah, p. 427

How Rav Kook Read the Newspaper

by Rav Moshe Tzvi Neriah

I never saw Rav Kook sitting and reading a newspaper. Every morning, after prayers, on his way from the beis medrash to his room, while he was still in tefillin and tallis, he would stop at the window opposite the door of his little room, where the newspaper, Doar Hayom, was placed regularly (and into which we too would peek while Rav Kook was giving his lesson in mishnah to the laymen’s minyan).

Rav Kook would pick up the paper and quickly scan the outside pages—and at times the inner pages as well. At most, he devoted a few minutes to this. In this way he completed his daily newspaper reading.

[It goes without saying that the newspaper of Rav Kook’s time had no immodest illustrations and no degraded, sensationalist articles.]

Only once did I see him read the paper with gravity, sitting down. This was a special edition of Doar Hayom presenting the White Paper of Lord Passfield, which gave the deathblow to the Balfour Resolution [which had presented the British government’s support of a Jewish state].

This edition appeared in the evening. When Rav Kook’s son, Rav Tzvi Yehudah, saw it on his way home from the yeshiva, he brought it immediately to his father. Rav Kook read the words carefully, and immediately upon finishing composed a sharp response, an inspiring proclamation, a powerful statement to the nation: “my great people, the nation of the living God and eternal King.” It was sent to the printer that evening. The next day, even before the responses of the national organizations were published, Rav Kook’s statement had already appeared in Jerusalem on the poster boards.

In this way, Rav Kook strengthened the depressed spirits upon whom the White Paper had descended like a shock.

Likutei Harayah, pp. 428-29

In the months of Rav Kook’s final illness, when he was offered him a newspaper, he refused to look at it.

He said: “In essence, I have no connection to ephemeral events, but I am given over to deep thoughts of eternal life. However, my position and responsibility obligated me to keep up with events and to know what was happening. But in my present situation, I am free from this, and I can devote this time to learning Torah.”

Likutei Harayah, p. 429

The Stature of Rav Kook

by Rabbi Gedaliah Aharon Koenig

I heard my father, Rabbi Eliezer Mordechai, praise Rav Kook a great deal and speak of his genius and piety, from the time that I was young until I became father to my first-born daughter.

And with my own eyes, I saw him protest against any insult to Rav Kook. With my own ears, I heard him cry out with all his strength in his old age, out of a true pain in his heart, against the abuse of Rav Kook’s opponents.

This was the story:

In the summer of 5692 (1931), my brother, the first-born of my mother, Rabbi Yosef Hillel, was engaged to the daughter of Rabbi Tzvi Blau, the brother of Rabbi Moshe Blau.

About two weeks before the wedding, a few young men from the bride’s family came to visit my father. He welcomed them graciously. It was his custom to receive everyone who came to his house and offer food and drink—and these were the bride’s relatives. He assumed that they had come on some errand from her parents regarding the wedding plans.

But they began speaking sharply. They told my father, “We have heard that you visit the house of Rav Kook. We are informing you that if you do not break your connection with him, we will call off the wedding.”

When he heard this, my father was shocked. He didn’t argue with them at all. Instead, he immediately got up from his chair and shouted at them: “Low-lifes! Whom are you talking about? Such a holy man of Israel!” He lifted the chair as though he were about to throw it at them, and forced them out of his house.

The men began to apologize that they hadn’t meant to upset him. But my father stood firm: “My own pain I forgive you. But when you speak against a man who is so noble, who is head and shoulders above everyone else—that I do not have the authority to forgive. And I no longer want to see your faces.” And he closed the door and left them outside until they left.

It later became clear that those men had acted of their own accord, without speaking to the in-laws....

I also heard from my maternal grandfather, Rav Shmuel Yaakov, that when he once went to a pidyon haben with a friend, he was astonished to see Rav Kook and Rav Chaim Sonnenfeld [who were ideological opponents] sitting together at the head of the table.

My grandfather was even more astonished when Rav Kook led the grace after meals. He held a goblet of wine. When a few drops spilled from his hands, Rav Sonnenfeld placed his hands under Rav Kook’s hands to receive those drops, and he licked them repeatedly.

My grandfather told me that from that time forward, he never believed any slander against Rav Kook. When he told me that story, I was young. The story is so deeply engraved in my mind that I cannot forget it. It sometimes seems to me that I myself saw the incident.

This is what I know from my parents regarding the sanctity and truthfulness of Rav Kook.

I understood this matter more when I grew up and came close tot he teachings of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, “a river flowing from the wellspring of wisdom.” I saw how the Evil One incites dissension in Israel, particularly amongst the wise and righteous of the generation. I saw how important it is to disbelieve any slander that is spoken about any unique one among them....

(Rabbi Koenig was one of the most respected leaders of Breslov Hasidism of the previous generation)

Likutei Harayah, pp. 161-63

Straw

by Simcha Raz

When Rav Kook became chief rabbi of Jerusalem, members of the extremist circles rose against him and harassed him. But Rav Kook was, in the words of the sages, like those “who are insulted but do not insult, who hear themselves reviled but do not respond.”

Once, his enemies were especially provocative and insulted him publicly. The city was in an uproar. But Rav Kook, as usual, overlooked the insult and remained silent.

“Rabbi,” those close to him asked, “to such a degree?”

Rav Kook responded, “I will tell you that in my heart, I know that I am not fit for the rabbinate of Jerusalem. Who am I to sit upon the rabbinical chair in the holy city, most of whose inhabitants are wise men and scholars, the masters of the generation and the pious of the world?

“I am like a man who puts on shoes that are too big. What does he do? He stuffs them with straw. And thank God, here in Jerusalem we have a good deal of straw. And by its nature, straw is prickly....”

Malachim Kivnei Adam, p. 201-02